Why doesn't India export more mangoes?

Or avocados, or cacao, or...

Summer in Mumbai. Harsh sunlight beats down, with nary a cloud in the sky to shade the sweating Mumbaikars. In a busy market, vendors shout offers, flies buzz around plates of pani puri, and stray dogs sleep in the middle of the road (entirely unruffled by the cars that whizz just inches past them). And there, to the side, colorful cardboard boxes are being unloaded from the cavernous back of a truck. People notice, start looking. Children cluster around. Even the flies hover, realizing something’s up. And they all see one thing – the time has come at long last.

That’s right. It’s mango season.

So, I love mangoes. Everyone around me loves mangoes. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t love mangoes (but I pity them).

My home city of Mumbai, India’s economic hub, is a land of eye-popping inequality where some of the world’s wealthiest people live a literal stone’s throw from some of its poorest. Few things truly unite the richest billionaires and the poorest laborers, but one feeling reliably crosses that divide: the eager anticipation of mangoes. Every April, the city rejoices when boxes full of bright, plump fruits finally populate store shelves and street carts, bringing blissful relief from the sweltering tropical heat. Beloved of figures from Alexander the Great (supposedly) to the Mughal Emperor Akbar, mangoes are considered a sacred fruit – a symbol of pleasure and good fortune.

How tragic, then, that so few outside India will ever bite into an Indian mango. Instead, walk into a supermarket in Canada or Germany, and you’ll see shelves full of ripe, plump mangoes from Mexico and Peru. Mangoes are relatively recent transplants to these countries – but they now dominate the mango trade to the high-value markets of North America and Europe. Elsewhere, Brazil and Thailand have made steady gains. In exports, India doesn’t even break the top 5. We grow 4 in every 10 worldwide – but almost all of those disappear down the gullets of eager, hungry Indians. We export less than a single percent of our production.

It’s not just distant South America that’s ramping up their mango game. Mangoes used to be such an exotic rarity in China that a cult briefly formed around them at the height of the Cultural Revolution; the zealous students running the movement preserved them with wax and built shrines on which to display them. Now, they grow enough to rapidly scale up exports – according to some reports (and the Chinese government’s own data), they might exceed India! We continue to fall behind our rivals in selling our most beloved fruit to hungry consumers worldwide, thereby failing to profit from a global market worth over $3 billion for fresh mangoes alone.

And we take that personally. When a shipment of Indian mangoes was recently turned away from America in May for supposed documentation problems, the incident made headlines across our country. Against the scale of our economy, Mangoes aren’t a truly significant export for us. At ~$60 million a year (for fresh mangoes), they’re a blip in our overall export revenue. We export twice as much in car parts to America alone, and over 600x more in textiles worldwide. But mangoes are different – they’re a proud symbol of India, our national fruit, admired around the world for thousands of years. In that respect, our failure to truly put our pride and joy on the plates of the world is galling.

But mangoes are just the start. Our sluggish mango exports are symptomatic of our general failure to seize high-value agricultural exports. The country’s diverse climates and soils, and experienced agricultural workforce, should lend themselves to growing a medley of high-value export crops – we’re just not growing them.

Cacao exports from India, for one, have remained negligible despite an unprecedented doubling of global prices in recent months. There were actually brief, earlier efforts to grow the bean for export in the 1970s, which were strangled in their crib by logistical issues and a global glut that depressed prices. But thanks to our tropical climate and geographic position, India is ideally placed to grow cacao, which can only really be grown in the ‘cacao belt’ — a narrow band around the equator.

While some is grown in South America, and some in Asia, the African countries marked in red account for the majority of all cacao production. But for how long? Many of these places are, unfortunately, politically unstable (and sometimes active conflict zones), which isn’t conducive to exports. And despite efforts, a lot of cacao is grown with what’s effectively slave labor; international buyers have been pressured to cease dealing with these places unless the cacao can be certified slavery-free (a few certifications, like Fair Trade Cacao, exist for this).

India’s rural labor situation isn’t perfect, but it’s not slavery - we easily meet certification requirements to export to the wealthy West. We’d also find it relatively easy to meet other standards, like the current European Union rules that limit imports of cacao linked to deforested land. This gives us a huge leg up - there’s nothing stopping us presenting ourselves as a more stable, more ethical alternative to the current top cacao sellers.

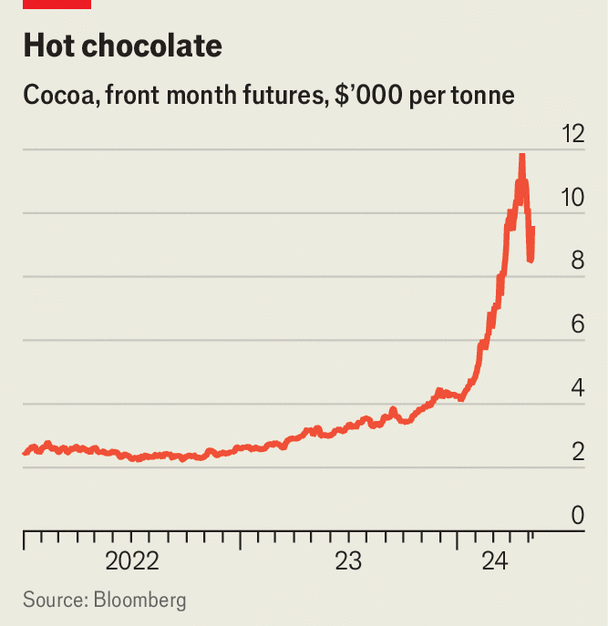

And it’s so lucrative! Cacao demand continues to climb rapidly worldwide, and supply hasn’t kept up. Starting 2023, chocolate demand spiked; meanwhile, bad weather conditions hit the harvest in top producers like Ghana and the Ivory Coast. The result?

While prices have been erratic this year to date, they remain at multiples of their 2023 levels. There’s a huge gap in the market waiting to be filled - but India isn’t in a position to fill it. We just don’t grow enough cacao.

Meanwhile avocados, the fruit du jour of the last decade, are grown so little in the country that India has specifically sought out import deals with South American producers to keep domestic prices down in the face of climbing homegrown demand. When fast-growing Mexican fast food chain California Burrito wanted avocados, they had to resort to growing 500 trees of their own. As one might guess, the country exports almost no avos, missing out on a market that by some metrics is worth $20 billion worldwide and growing fast – instead, we spend our hard-earned forex buying them so I can make my weekly bowl of guac.

So where does India’s reputation as a prominent agricultural exporter come from? We are one – just not in high-value products. The majority of our crop exports still lie in low-value, high volume products like wheat and rice. These have historically been seen as a safer bet by farmers owing to predictable global demand and the safety net of official price floors. In recent years, however, these staple exports have been an unsteady prospect; prices have fluctuated with global events like the War in Ukraine, and the sector has seen export bans and stoppages by the Indian government to tame food inflation in India’s crowded cities. Arguably, high global wheat prices have failed to benefit most Indian farmers anyway: according to economists like Jean Drèze, real (inflation-adjusted) farm wages have stagnated since 2014, a fact unchanged by record wheat and rice exports in the chaotic years of 2021 and 2022.

A large part of the problem with high-value products lies in the lack of public or private investment into meeting the quality and safety standards of destination countries. Just look at mangoes. Countries like America demand that the fruit be treated with radiation before it’s shipped. For the longest time, India had only a single official facility to irradiate mangoes. While we’re now spinning up more facilities, irradiation remains expensive – at INR 35/kg according to one source (though this may vary), it eats into farmer profit margins, and we haven’t scaled up irradiation enough for economies of scale to to bring down costs significantly.

Quality problems led the EU to ban Indian mangoes for a year in 2014, while America refused to approve imports from 2019 to 2022. This quality problem reaches beyond just fruits – India’s vaunted spice exports, which bring in billions of dollars a year, have seen contamination allegations from multiple countries that threaten the entire industry and could lose us hundreds of millions a year in export earnings – a much higher number than our overall mango exports.

But the problems start even earlier than the quality checks. Farmers need to actually get the goods to an irradiation facility, and India being what it is, freight can be expensive and difficult – per the Times of India last year, transport for mangoes can cost 2x their actual retail price. Transport channels are also largely unrefrigerated – we don’t have the kind of cold chain penetration for storage and transport that countries like Mexico have invested heavily in to bolster exports. According to organizations like the UN’s FAO, as much as 1 in 3 fruits or vegetables grown in India is lost to spoilage after harvest, and the ones bound for export are no exception.

What makes the entire situation more tragic is that we know India is eminently capable of producing success stories in high-value agricultural exports. Just smell the coffee.

A generation ago, India exported almost no coffee. This year, almost $2 billion worth will be shipped out of Indian ports, a number that’s doubled inside of a decade and is showing no signs of slowing down – the state of Karnataka just saw coffee export earnings rise 60% in a single year.

The interesting thing is that the quantities of coffee being shipped out haven’t changed much. Our coffee exports have surged in value, not weight. Indian coffee growers aren’t trying to make money on volume. Instead, they’re aggressively pursuing high-value markets and moving up the value chain. They’ve taken advantage of the global price rally – off increased global demand and weak production in major players like Brazil and Vietnam – to ship to rich markets, and invested in value-additive processing to push up sales prices. Combine that with smart branding (‘estate’ brands for one) and quality grading to meet export standards – and suddenly Indian coffee commands much higher prices than it used to.

The Coffee Board deserves a mention here. A venerable institution that predates India’s independence, the Board has lately been assisting producers with grading and quality assurance, helping them comply with export standards, and easing the export process by moving towards instant, all-digital licenses. Every Indian export organization could learn a lesson from what they’ve done: remove obstacles to export, don’t add new ones.

I don’t see why we can’t reproduce this for avocados, for cacao – and for mangoes. And we should. It’s not just about raw numbers; we’re always going to make much, much more money exporting iPhones and T-shirts than mangoes. But high-value agriculture has a disproportionate impact on Indian farmers, who have been in a sustained crisis for years because India’s economic growth has in many ways failed to make its way to them. Finding high-value agricultural export niches, and aggressively pursuing them, is an imperative; it’s not particularly expensive, holds out the prospect of very high ROI, and will direct its profits to the people who need them most.

It’s about time.

I’ve had many of these exact same conversations about mangos and avocados in Kenya. Lots of potential for those crops!