Why are India's youth still flocking to civil service exams?

What the continuing UPSC craze says about the country

In the Bollywood surprise hit 12th Fail, a young man with dreams of joining the Indian Police Service journeys to the big city to study for the exams. The first thing he sees: flocks of people filling the street, packed so tightly there’s no room to breathe. Textbooks, both real and pirated black-and-white copies, in every hand. Signs hung from every wall and lamppost advertising the best coaching classes in the country. A riotous throng, thousands strong, all with the same dream – all of them competition.

He turns to his friend, a fellow aspirant. “There’s so many of them. How could we ever get through?”

Poor kid. He really has no idea.

On Sunday the 25th of May last year, over 600,000 people queued up at over 2,300 locations across India. Many of them had been preparing for this day for years. Many had already been through this once, twice, even five times or more. Some were doing this for the first time, surrounded by weary veterans of this crusade. And all of them were after the same thing.

That’s right, folks. It’s the UPSC Prelims. God help them all.

A quick primer: India recruits its most of its central civil servants through a single competitive exam process, the unimaginatively-named Civil Services Examination. The actual number of services one can join by passing the exam is expansive – ranging from the Railway Management Service to the Corporate Law Service – but the holy grail for most applicants lies is the trio at the very top: the Police Service (IPS), the Foreign Service (IFS) and the sanctum sanctorum, the Administrative Service (IAS).

If you’re Indian, you probably already know this even if you’ve never considered taking the test. That’s because these exams are some of the biggest events in India. Rising applicant numbers are the subjects of countless newspaper headlines every exam season, ‘toppers’ who rank first become instant celebrities, and an entire coaching industry worth hundreds of millions of dollars has sprung up to beat knowledge into the heads of the horde of hopefuls every year. In recent years, Bollywood has cashed in on the craze with multiple popular movies and streaming shows about the exams and their hopefuls.

All in all: it would be an unpardonable understatement to say the exams are a big deal. And that raises an interesting question – how did they get so big? What explains the explosion of applicant numbers in recent decades? And what has this done to India?

Where did civil service exams come from?

Like any randomly chosen plastic good, electronic device, or fast-fashion crop top: China. Probably.

As far as we know, competitive civil service exams developed during the Tang Dynasty in the 600s, and matured during the Ming in the 1600s as a tiered system. Young, elite Chinese men (no women allowed!) hoped to pass each level of tests, from town to province and finally to the exams, held by custom at the Imperial Palace in the capital and supposedly observed by the Emperor himself. Passing that final stage conferred a degree known as jinshi, with the names of these hallowed scholars posted on the walls for all to see. Town criers rode through the streets shouting the names of these revered few, and their hometowns would throw lavish celebrations on hearing the news.

Just passing any level of the exams conferred a number of attractive privileges – wide tax exemptions for life, freedom from conscription, lessened punishment for crimes. But the real draw remained the prospect of a job. Jinshi holders were catapulted directly into the top ranks of the Imperial administration; many would go on to serve as powerful scholar-bureaucrats, shaping the course of a dynasty and sending reverberations through history.

Passing the exams was a big deal. If you were a member of the literate Chinese elite (and by social mores barred from anything as ugly as commerce) it was the only deal around.

What were these intrepid scholars being tested on? Statecraft? Economics? The law? Nope. Confucius (Kǒngzǐ to his friends) – specifically, the Four Books and Five Classics, which are as close to holy texts as Confucianism has. If you, a hot-blooded Song-era literatus with dreams of power, wanted to ace the exams and take that first step on the road to fame, you needed to know these nine texts inside out.

And I mean really know them. There are over 500,000 characters that make up these books, each one representing a word, and candidates were expected to memorize every single one. A number of questions were of the form ‘fill in the blank’, where a random line from one of the texts would be given with the middle characters removed; the candidate had to reproduce the entire line, with no mistakes, and identify exactly which text it came from and where (a millennium later, we use similar tasks to train large language models like ChatGPT). Other questions would be sneakier: for instance, a question might provide a single line from the texts, and instruct the candidate to provide commentary on the line that follows it.

If this seems like a system entirely divorced from the practicalities of governance, that’s because it was. For centuries, there was even a poetry component! The Chinese imperial exams weren’t really about proving your knowledge of governance; they were about demonstrating your fluency in the intellectual culture of the Chinese elite. Granted, it wasn’t all totally irrelevant – Confucius and his disciples had much to say about taxation, jurisprudence, and statecraft – but the emphasis was never on practical problem-solving ability.

By the later years of the Qing, the drawbacks of this system had become abundantly clear in the face of increasing pressure to modernize China. Furious arguments raged over the role of the exams, and the insular clique of conservative scholar-bureaucrats they created, in holding the country back from progress. The last few decades of exams actually experimented with adding in a few questions of relevance: the 1904 exams, the very last ever held, featured a section on current political issues amidst the usual Confucian discussions. Questions included:

“日本变法之初,聘用西人而国以日强,埃及用外国人至千余员,遂至失财政裁判之权而国以不振。试详言其得失利弊策.”

That is, roughly:

“When Japan first undertook its reforms, it hired Westerners, and the country consequently became stronger. Egypt, on the other hand, employed over a thousand foreigners, and thereby came to lose control over its own financial and judicial institutions, with the country then failing to prosper. Try to explain in detail their successes and failures, advantages and disadvantages, and the policies involved.”

This sort of question is probably recognizable to any Indian aspirant - it’s not far off from the ‘short essay’ questions you’d find in a UPSC exam today. For the Qing, it came too little, too late, and the exams were abolished in 1905, never to return.

But they lived on! Like so many other exotic relics from around the world, the British Empire admired this system and thought it would be nice to have at home as a conversation piece. So the exams took on a new life as:

The Indian Civil Service Exams

Until the 1850s, India had been governed largely by the British East India Company, a (technically) private enterprise whose top administrative staff were recruited in London through systems of influence and patronage – new recruits required a nomination from one of the company’s 24 directors, so it was really a matter of who you knew, not what. When the British government started muscling in, it forced the Company to end patronage and recruit its staff through competitive exams.

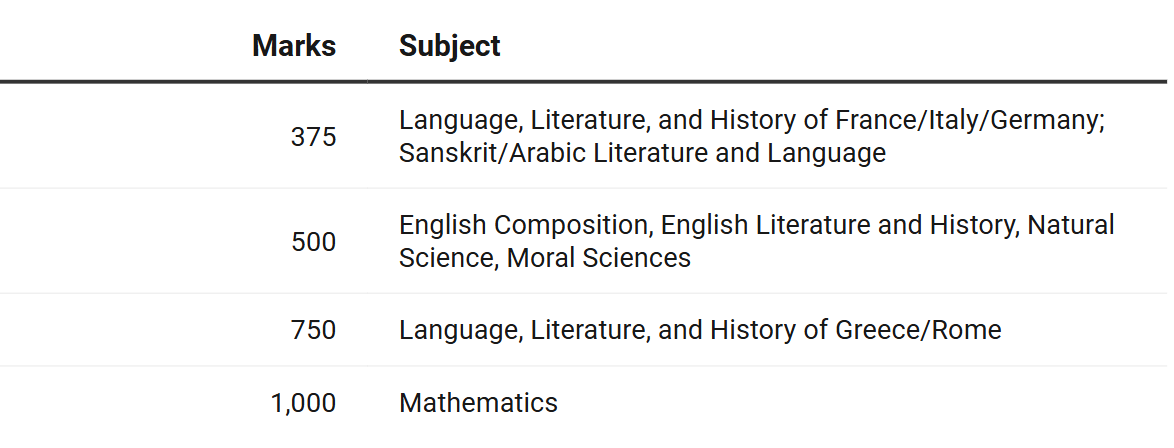

Interestingly, the Charter Act of 1853 – the law that began transferring many of the Company’s functions to the British government – specifically allowed Indians to take the exams. In practice few ever made it. Why? Well, here’s the grading breakdown for the very first exams, held in 1855.

Keen-eyed readers will notice a few puzzling things. First, Greco-Roman subjects (including two dead languages) weigh twice as much as the optional paper in Sanskrit/Arabic. Second, the exam did not test for knowledge of any of India’s actual spoken languages. One would think being able to communicate with the people you govern would be more useful for a civil servant than being able to quote Thucydides; clearly, the British government took a very different view.

Small wonder that successful British candidates outnumbered Indians by some 20 to 1. It didn’t help that exams weren’t even held in India until 1922. The first Indian to pass the exams was Satyendranath Tagore (brother to the famed writer) in 1863, after years of intensive study with the resources of a wealthy family behind him. A handful of others joined him in the decades until the system was overhauled by the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms, which aimed to address rising popular discontent by making the civil service 50% Indian; exams were finally held in India, and the content was reworked to be more relevant to the actual governance of the country. The reforms also set up the predecessor of the body that still runs the exams, the Public Service Commission.

And then, in 1947, the Empire packed up and left. The ~1000-odd Indian Civil Service was just about half Indian on the eve of Independence. While many British civil servants were invited to stay on by the new nation, almost all of them chose to leave. The Civil Service was left to reconstruct itself as completely Indian. And that’s exactly what it did, renaming itself the Union Public Services Commission (hence the famous UPSC acronym) and creating its own system of exams and interviews to decide who would help build this new nation.

I’m not sure they foresaw just many people would one day apply. I’m not sure anyone did.

Which raises the question:

Where are all these applicants coming from?

Shortly before independence, there was 1 Civil Service officer for every 300,000 people in India, which then included present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. Today, that ratio is about the same, with about 5,500 serving IAS officers against a population of close to 1.5 billion. New vacancies are added slowly, if at all; the IAS is actually operating at about 1,000 posts below its allowed maximum.

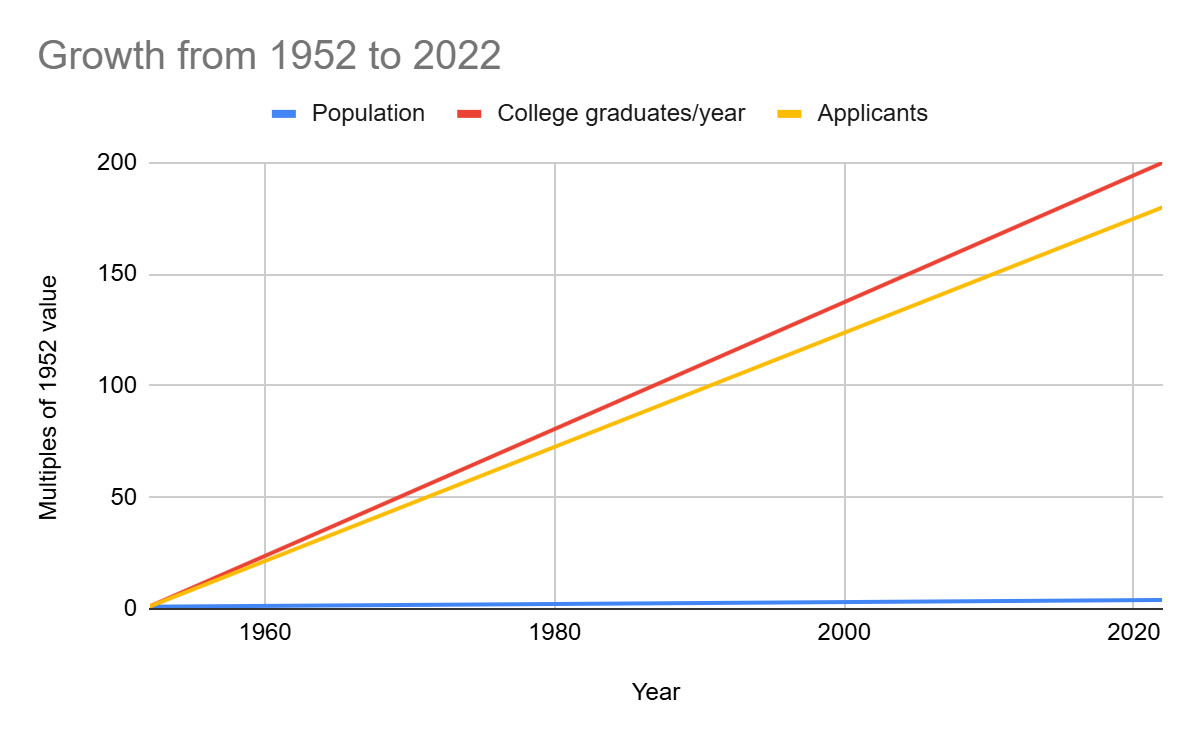

So if the number of positions has remained about the same, relative to population, why are they so competitive today? What’s really changed is just how many people are trying to get those jobs. The second annual report of the then-renamed UPSC, which covers 1952, is illuminating. About 3,200 candidates actually appeared for the combined competitive exam meant to recruit for the IAS, IPS, and other Central Services; after a subsequent round of interviews, 59 of them were ‘declared successful’, which meant about 1 in 55 exam-takers ended up finally getting through. That’s an ultimate success rate of ~2%, which would still make it one of the most competitive recruitment processes in the world today.

Fast forward 70 years to the year 2022. India’s population has multiplied by 4; the number of people actually taking the exam, on the other hand, has multiplied by 180. In total, 933 candidates were ‘recommended’ for posts in 2022, which gives us a ratio of over 600 disappointed exam-takers for every success – a pass rate of one-sixth of a percent.

(Note: In any given year, about half the people who apply for the preliminary exam don’t really take it. To make things more precise, I’m only using figures for people who do show up.)

And a lot of this increased competitiveness is comparatively recent. Between 2002 and 2022, India’s population grew by about 30%. Meanwhile, the number of people appearing for the exam grew by 250%. Why?

For one thing, it’s easier than ever to prepare for the exams. The Internet has democratized the resources needed to study. Years of past question papers are available, from independent sources and the UPSC’s own website; study guides and model essays are freely downloadable, or available with an online subscription. This doesn’t stop legions of aspirants from frequenting coaching centers and full-time prep classes, but it does mean taking that first step is easier.

Plus, India is now younger than ever – two in every three Indians is below 35. The exam is only open to applicants between the ages of 21 and 32 in the general category, up from a maximum age of 24 when it started out. That group constitutes a larger fraction of the overall population today than at any other time in our history.

But perhaps the most important single change has been education. To sit the exam, you need to have at least a Bachelor’s degree or equivalent; as far as I can tell, this has been a requirement since the very earliest days of the system. In 1947, when we became independent, India saw on the order of 50,000 people a year graduate with Bachelor’s degrees (going off a figure of about 200,000 in total enrolled in higher education). Today, that number has multiplied by a factor of 200 – it’s grown 50 times faster than the general population. You’ll note that this is in the same order of magnitude as the multiplication in the number of exam-takers.

Combining all this, it’s easy to say as a first-order estimate that when you control for these factors – especially education – today’s applicant numbers make perfect sense. And yet, I don’t think that’s all of it. Because our number of qualified applicants has exploded since the 1950s – but so has our private sector, which employs the vast majority of educated Indians today. Why is it that, in the face of steady economic growth that multiplied our GDP by a factor of 5 between 2000 and 2020, the proportion of people trying to get a government job has only grown?

You’d expect, intuitively, that proportionately fewer educated Indians would favor the civil service – with its fairly low salary ceiling (INR 250,000 a month for the nation’s top bureaucrat; even accounting for the perks, the top levels of industry pay much more) and extremely difficult entry process – over the private sector. But that hasn’t happened. Application numbers increase every year, still growing faster than population. What’s going on?

When do government jobs get more popular?

Why do people lust after government jobs? In countries like India, government positions have long been seen as high-prestige, reliable, and above all secure – unless you mess up spectacularly, you have a job for life, and a pension after you hit mandatory retirement.

In China, this is known as the ‘iron rice bowl’, and has been a thorn in the side of reformers since the days of Deng Xiaoping. For a while, China’s booming economy lured people away from government jobs; the civil service exam, the Guokao (not to be confused with the equally competitive college entrance exam, the Gaokao), actually saw total applications fall by a over 100,000 from from 2013 to 2014, both years in which the country’s GDP grew by almost 8% and its population by over 7 million.

Now, with economic growth slowing and harsh private-sector hours taking their toll, China’s working-age youth are quietly rebelling by ‘lying flat’ – gravitating toward stable work that requires the bare minimum of effort and giving up on fiscal ambition. Where else to look but government jobs? Civil service applications are once again high and still growing. China, too, puts an age ceiling on applicants, recently raised from 35 to 38. With an aging population, the median Chinese is already too old to apply – which makes it remarkable that applicant numbers are soaring even as the eligible population is shrinking. Almost 3 million people in China sat the exams in 2025, a number that has doubled in a decade.

South Korea, while much wealthier in comparison, has also seen civil service applications fluctuate with its economic fortunes. In 2019, as the economy slowed amidst a US-China trade war, applications for government jobs started increasing. They surged in 2021, in response to a post-COVID hiring slump. By 2025, applications had fallen by half, hitting their lowest level since 2017 (a year in which the country’s GDP grew by a respectable 3.1%). This is despite a comparative slowdown in job growth at South Korea’s chaebol super-conglomerates; for now, the country’s youth are optimistic about opportunities outside the public sector.

In Japan, the late 1990s and early 2000s saw real wages stop growing entirely; the civil service suddenly became everyone’s dream again as stable, well-paid jobs became scarce. As things got better, that trend quickly reversed: after 2012, applications for government jobs dropped precipitously, falling over 30% over the next decade. As Japan’s economy slowly rebounds from its lost decades after the crisis of 1995, top graduates of the elite Tokyo University no longer flock to the civil service, and the Japanese government is exploring ways to tempt the country’s best back to government work.

The pattern is clear. When the economy’s doing well and job growth is high, people move away from government jobs. When the economy slows down, people rush for the stability of the civil service.

That is, everywhere except India.

As we’ve seen, Chinese demand for government jobs once dropped by almost 10% in a single year. The only comparable drop in UPSC exam-takers in recent memory was recorded in 2020 – not coincidentally, the year in which the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the exam. And this drop didn’t even last the entire pandemic! Within two years, numbers had more or less recovered - and they’re still going up. So…

What Makes India Different?

Is it just an unquenchable mania for government work? A patriotic fervor? A social expectation. Maybe – but there is one more explanation. We’ve already seen that China’s demand for these government jobs dropped sharply in just one year, after 2013. I think China’s meteoric growth at the time had something to do with it. But I suspect there was one more factor. See, something else happened in 2013.

In late 2012, Xi Jinping ascended to the lofty post of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee – the position that brings with it de facto leadership of the country. Shortly afterward, he made corruption a key part of his agenda; he promised to go after the ‘tigers’, Party leaders enriching themselves, and the ‘flies’, low-level bureaucrats. Over the next two years, some of China’s highest officials were convicted of corruption, thrown out of the Party, and sentenced to long prison terms.

As for the ‘flies’? Between 2011 and 2013, the number of low-level officials punished went up by over a quarter; some 180,000 were punished in 2013, the first full year of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. By 2016, that number more than doubled to 415,000, making it abundantly clear that Xi was very serious about it.

The campaign has been extensively studied by economists and political scientists, and the common conclusion is: the number and quality of applicants decreased because the perceived monetary value of the jobs – most of which was ‘informal’ i.e. corruption – had decreased. Smart, ambitious would-be applicants realized they’d make less money off corruption, and would be more likely to get caught, so they decided it wasn’t worth the payoff.

Meanwhile in India, the UPSC continues to attract fast-increasing numbers of applicants every year, among them some very high quality candidates. This means one of two things:

a) This China model doesn’t apply here - even with wages in the private sector increasing while government salaries remain stagnant, educated Indians are just so full of patriotic pride that they don’t mind the low pay for the chance to make a difference to the country.

OR:

b) The China model still applies – and educated Indians know that the real wages of a government job far outweigh the possibilities of the private sector. Despite periodic anticorruption campaigns, the perceived ‘corruption premium’ of these jobs remains very, very high, and the possibility of being caught and punished remains very, very low.

And this is pretty well known – everyone assumes these jobs come with a corruption premium way above their nominal salaries. Corruption is endemic in India at all levels of the bureaucracy. Is that where all these applicants are coming from - people wanting their own piece of the pie?

The Protection Premium

There’s another aspect to it that I think lots of Indians recognize, but few really articulate, that makes India very different from China.

I started this by telling you about 12th Fail, the movie about a young man with dreams of joining the Indian Police Service. That dream didn’t come out of nowhere – early in the movie, his brother is framed and locked up by the local cops on the order of a local elected official. Our plucky protagonist begs a recently-arrived Indian Police Service officer to intervene; awed by the officer’s ability to see justice done with just a few words, he resolves to become one himself.

Great story about an inspiring, upright police officer, right? Sure… but why was his intervention needed? Unfortunately, because we live in an India where a random local politician can order you arrested, your rights can be ignored, the rule of law is weak, and unless you’re wealthy or powerful, there’s pretty much nothing you can do about it. Or maybe a friendly IPS officer will show up to save you – there’s less than 5,000 in the country, so good luck with that.

Naturally, this factor is less relevant in countries where you can rely on the government, police, justice system, and bureaucracy to do their jobs with relative impartiality – and that’s reflected in the number of people who want in. Over in America, despite the police’s reputation for power and impunity, many police forces have trouble getting enough applicants and run understaffed. The UK has similar issues, as do many industrialized nations. Even though salaries are often generous, there just isn’t any point being part of the police when they’re so constrained – you don’t often need to be part of the government to be safe from the government.

Meanwhile in India, even low-level constable posts routinely see over a hundred applicants for every vacancy. Last year’s critically-acclaimed movie Homebound features two young Indian men, one a Dalit and the other a Muslim, taking the state-level police exam with a horde of other hopefuls because they believe the power of the uniform will erase the disadvantages of their caste and religion; nobody pushes around a police constable.

The private sector is no shield in India; despite strong economic growth over the last decades, any private sector operator is vulnerable to interference from the state that can, in extremis, lead to state-sponsored ruin. The only shield is being part of the system itself.

That’s why our system isn’t like China’s. Not because the Chinese state is less oppressive, but because being part of the government doesn’t actually protect you from the government. China is, famously, one of very few countries in the world that hands down death penalties for corruption – those sentences are often ‘suspended’ to just life in prison, but the possibility is very real.

Even at the lower levels, the price of petty corruption is high. In 2013, a bridge collapsed in Jiangyou; the resulting investigation put a local official in prison for 14 years, amidst other convictions. He was still luckier than a deputy local Party secretary who was sentenced to death (albeit suspended) for taking a $20,000 bribe from a bridge contractor in 1999. In post-Deng China, taking a bribe to approve a shoddy bridge will see you punished; China’s government, from the top ranks to the bottom, is periodically purged of those embarrassing the Party. Being in the system won’t save you from the system – in some ways, it makes you even less safe from scrutiny by the Party.

Meanwhile, in 2022, a bridge collapsed in Morbi, Gujarat, killing 141. The local municipality’s chief officer was suspended, but seems to have suffered no other consequences; the municipality has denied any responsibility. According to Indian law, a public servant can’t be prosecuted without specific sanction of the government, either state or central depending on where they work; in an incisive editorial, Kingshuk Nag, then an editor with the Times of India, makes it clear just how difficult that is. In India, the system protects its own.

People like money and power, but people also like to feel safe – to know that if the weight of state power ever pits itself against them, they have options. I suspect a lot of people feel like you can’t beat them, but you can join them, be them.

And so, every year, over half a million people line up for a shot at entering the ranks of the powerful. What does it cost us?

The Hidden Costs of the UPSC

A bare handful of the 100,000s who try every year will make it through the UPSC. What of the rest – those who’ve spent years prepping for these exams, only to fall short? What happens to them afterward?

We don’t know the answer for the UPSC but we can guess, thanks to Kunal Mangal. While he was a graduate student at Harvard, Mangal tracked the outcomes of people who tried to get into the civil service of the state of Tamil Nadu, through its own exam system, right as it instituted a hiring freeze that multiplied competitiveness.

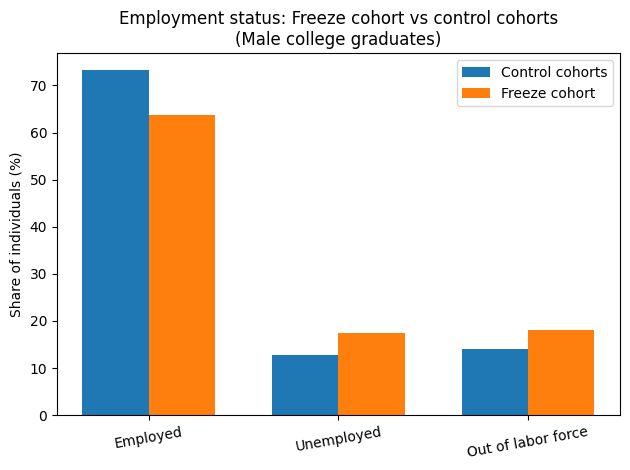

Mangal compared a particular cohort – the group of male Tamil Nadu residents graduating college during the hiring freeze – to the cohort that graduated college right after the freeze, as well as to the same population in neighboring states. While he had no way of separating out only the actual applicants, he believed recent college graduates were a reasonable approximation – apparently, a quarter or more of college graduates in Tamil Nadu apply for the exams. He then used household survey data to track this group’s outcomes over the years.

(Note: Mangal notes that he tracks only males because Tamil Nadu’s female labor force participation was low enough that it would be difficult to detect changes.)

The way Mangal sees it, this group of people took more time to study for the exams in response to the increased competitiveness – and therefore removed themselves from the labour force when they’d otherwise be early in private industry careers. There weren’t any major economic movements or demand-side shocks in Tamil Nadu during this period. Nor could the impact on their lives be ascribed to their failure to get the civil service jobs, since only a tiny fraction were ever going to make it through even before vacancies were reduced. The only real difference was this hiring freeze, and their behavior in response to it.

And the result? This group of recent college graduates had measurably worse outcomes in many areas even a decade after the exams. They were less likely to run businesses, more likely to end up in lower-quality private employment, and still more likely to report being ‘unoccupied’ well into their 30s. They were more likely to live with their parents or guardians, and less likely to have married or start families; their households had lower consumption numbers, a strong proxy for income. And remember, if Mangal is correct, all these dramatic disadvantages came from one source: the years they spent trying to get into the civil service.

To the best of my knowledge, nobody’s done something similar for the UPSC’s own exams; given that aspirants come from all over the country, any survey dataset trying to cover it would have to be massive and comprehensive. That being said, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if similar effects played out at the national level – and it’s baffling how little anyone has cared to look into the trajectories of failed UPSC aspirants. The news does the occasional piece about it, like this one from The Print, but there’s very little effort to track outcomes and figure out what becomes of these disappointed millions. Anecdotally, most probably end up doing alright (eventually), but in the counterfactual world where they didn’t decide to try for the UPSC, where might they have been? Sadly, we’ll never know.

The effects go beyond economic. Plenty of anecdotal data and small-scale surveys reveal sharp drops in mental health among aspirants. Newspaper routinely carry tragic stories of suicides among applicants after exam results are made public; overall student suicides in India rose 65% between 2013 and 2023.

Needless to say, very few people trying for the civil service are having a good time.

But there’s another aspect to this: what are the costs to the country? Civil service aspirants are an extremely selected pool. They’re young, since they have to be between 21 and 32 in most cases. They all have at least college degrees, making them more educated than 85% of Indian adults. And many of them are ambitious, driven, and hardworking. What this means is that every year, hundreds of thousands of the most potentially productive people in the Indian economy remove themselves from it by choosing to study for the UPSC instead.

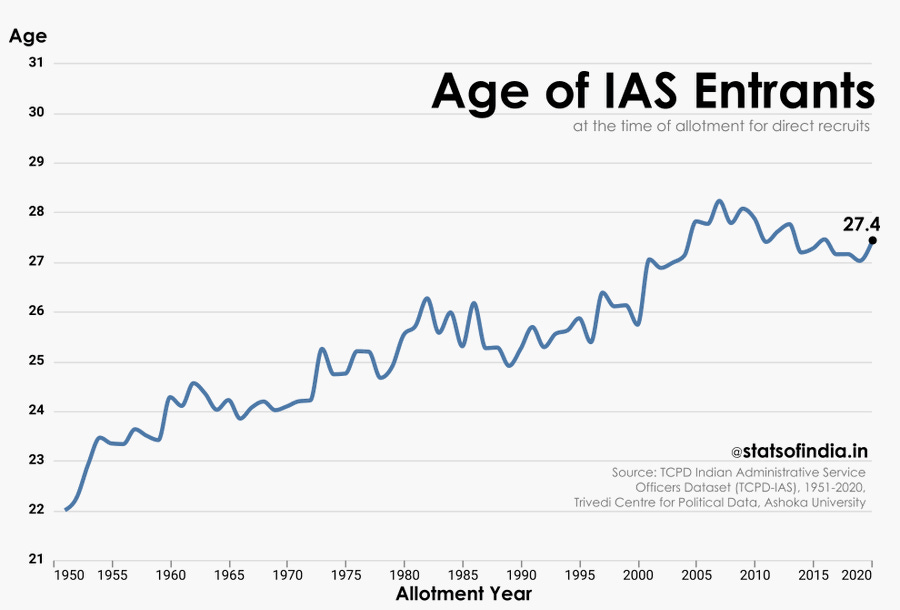

And for many of them, the process consumes years of their lives. These days, the average successful aspirant is 27, and has given the exam at least three times before getting through.

I don’t know what the total cost to the economy is. Nobody does – there’s no academic work on the topic at all. But I suspect it’s much higher than is comfortable to think about.

Whither UPSC?

Every year, the exams get more popular. Every so often, someone tries to fix them. A few committees over the years have recommended that the maximum applicant age be lowered to 27; among other reasons, data from across the world shows that civil servants who join later are less productive throughout their careers. The government has not done that, in large part because it would cut out a massive cohort of civil service hopefuls who’d find themselves aged out much earlier – apparently, the faint hope of getting through at the very end is worth preserving.

Other committees thought it would be a good idea to let narrowly unsuccessful candidates – those who got through everything except the interview – fast-track into other government positions not covered by the UPSC. This was implemented in part, but there aren’t many of those positions either.

There’s been talk about extending recruitment to professionals in their 40s, which is probably a good idea – plenty of other civil services recruit primarily from people who’ve already done a stint in the private sector, and are better off for it.

But small changes aside, the UPSC in its current form is probably here to stay. We’re entering an era of global economic uncertainty, and every productive, educated Indian will be needed. Unfortunately, that turmoil is probably going to drive even more of them to years of textbooks, tuitions, and tests. That should concern us all.

Of course, Bollywood – having finally found a topic that consistently gets them an audience – will probably keep making movies and TV about the process. In this, they’re not unlike the Chinese, who loved writing about the exams. The difference is, the Chinese weren’t always positive about them.

The 18th-century author Wu Jingzi, himself a disappointed applicant, wrote a famous novel, The Scholars, that is shot through with biting satire of the Chinese Imperial exams and their hopefuls. Characters include archetypes familiar to any Indian test-taker, like a miserly student fretting over the cost of a candlestick on his deathbed, and an expensive tutor expounding spiritual wisdom while shamelessly exploiting his students.

Amidst it all is Fan Jin, a hapless scholar who’s failed the exam time after time, and made himself a figure of scorn to his friends and family – who beat and berate him more with every failure. And then, he finally makes it. When someone tells him he’s got through:

“When Fan Jin heard the news, he clapped his hands and laughed. ‘Ha! I’ve passed! I’ve passed!’ Then he fell down in a dead faint.”

Fan Jin proceeds to go insane – laughing uncontrollably, running head-first into walls, and accusing the villagers of being demons. At his hour of triumph, the system has broken him.

Maybe that’s just what the UPSC is really testing – not how smart we are, or how prepared, but how insane we’re willing to be.

To offer an explanation as to why these exams used to include poetry and literature; it was to make sure that successful applicants, who would become administrators of the realm, were in tune with the values of the ruler, and that they would be more inclined to carry orders out.

Familiarity, it is hoped, would breed sympathy and loyalty.

Couple of thoughts:

1.

There is a regional angle here as well.

The educated from the most unproductive states take these exams at a higher rate.

Which further worsens the macro economic impact.

2.

The class/caste profile of successful candidates has changed. In the beginning the civil services were a preserve of certain groups like Kayasths and Brahmins from the south, Bengal, Kashmir. And similar urban communities like Nasranis.

While there was always an economic incentive, there was also a sense of public spiritedness in joining the civil services.

That has changed. Most people from these historically dominant groups today generally choose to emigrate abroad.

The class factor did create a sense of aspiration among other groups.

So general category selection is dominated now by mercantile and landholding groups. These were generally materially well-to-do communities that took up English education later and wished upward class mobility.

The selection among reserved categories is dominated by a handful of politically influential castes.

Reforming the system is tough due to entrenched lobbies but also due to a political economy that has developed around the exam.

We’re stuck in a sub-optimal but stable equilibria.